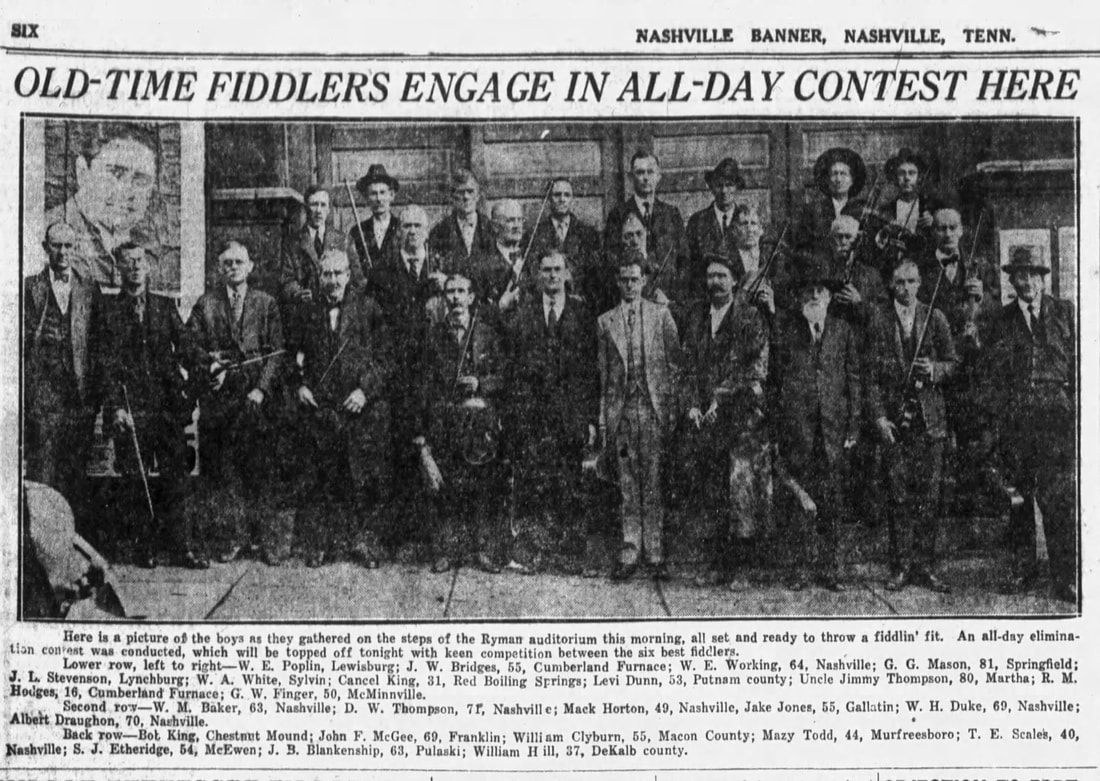

The January 19, 1926 Nashville Banner covered the Ford sponsored Tennessee old-time fiddle contest finals. Some 25 fiddlers, primarily from Middle Tennessee, competed for the state title. Numbered among them were John L. “Uncle Bunt” Stephens (incorrectly identified here as J.L. Stevenson), Uncle Jimmy Thompson, and Marshall Claiborne (incorrectly identified here as William Clyburn). Stephens and Claiborne would play for Henry Ford later that year in Detroit, with Stephens claiming victory in the national fiddling finals which probably never took place. Thompson, the more seasoned and perhaps most talented musician of the group, was famed announcer, Judge George D. Hay’s, first guest on the Grand Ole Opry. Earl Latta was a Ford man, through and through.

Latta was born in the Gravel Hill community of McNairy County, Tennessee in 1895, just two years after Henry Ford produced his first automobile. The young Latta took a job at 18 years old, servicing Model T Fords at a garage in nearby Selmer. Intelligent, a born salesman, and enamored of the new advances in personal transportation, he quickly absorbed a good working knowledge of the new motorcars and the burgeoning American automobile industry. Henry Ford was a role model for the budding entrepreneur, and Latta followed the auto tycoon’s career with great interest. What he learned, coupled with what he already knew about West Tennessee music, would serve him well in the years to come. When Latta shipped out for active duty in France during World War I, he had never been more than a few miles from his boyhood home. After completing a tour of duty he returned to Gravel Hill where a disagreeable turn in farming was enough to convince the young man that agriculture was not in his future. He moved to Selmer and resumed his lifelong love affair with the automobile as an employee at the local Ford dealership. By 1926 Latta had saved enough money to purchase his own Model A Ford coupe. He must have been a dashing figure—a young man with money in his pocket motoring about a rural Tennessee town where mules and wagons were far more common. The same year Latta bought his first automobile, an old-time music craze was sweeping the country. Curiously, the car and the craze sprang from the same fertile imagination. In the mid 1920s, Henry Ford began systematically promoting old time dance and music events—especially fiddle contests—through his rapidly expanding network of automobile dealers. With the Roaring Twenties well underway, Ford felt the excesses of the Jazz Age were eroding the simpler times and wholesome entertainments of his youth. He mobilized local Ford dealers who sometimes partnered with booster clubs, civic groups, or fraternal organizations to host old-time fiddle contests as qualifying events, inviting the winners to compete for state and regional titles. The Volunteer State naturally produced a respectable crop of fiddlers including John “Uncle Bunt” Stephens, “Uncle” Jimmy Thompson, and the one-armed fiddling sensation Marshall Claiborne who took top honors at Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium. The three Tennesseans then competed in Louisville, Kentucky for the “Champion of Dixie” title with Stephens and Claiborne supposedly advancing to Detroit for the finals. After that, things get a little more fuzzy. Several fiddlers—Stephens among them—apparently did play for Henry Ford at a Detroit gathering of Ford executives and dealers, but there is no record of a fiddle contest taking place, let alone the crowning of a national champion. Stephens, whose yarn spinning rivaled his fiddling, told Nashville reporters that he attempted to bow out of the contest with the excuse that he’d only split enough wood to last his family three more days. He claimed Henry Ford dispatched one of his agents to Lynchburg to provision the Stephenses with wood and other necessities, set him up in a private room at the Ford estate, and bestowed on him the title of national old-time fiddle champion. What really happened in Detroit is unclear, but a good Southern tale relies more on the quality of the story than the facts, so Stephens’s humorous version of events persists in Tennessee music lore. McNairy County was not left out of the fun. An “Old Fiddler’s Contest,” sponsored by the Selmer Parent Teacher Association, took place on April 15, 1926. Though advertising for the event never mentioned the local Ford dealer, the contest undoubtedly grew out of the national enthusiasm for old-time music touched off by Henry Ford’s thinly veiled social agenda. A deep regional music tradition in Southwest Tennessee, and an incredibly strong crop of local fiddlers, certainly wouldn’t have hindered matters. The winners of the Selmer contest were apparently never published, but you can bet fiddlers such as Con Crotts, Elvis Black and Waldo Davis were in the running. It is impossible to know if Earl Latta was present for the McNairy County fiddle contest, but his longstanding affiliation with Ford, coupled with his personal affinity for old-time music, make it hard to imagine him sitting it out. The old-time music and dance craze left an indelible imprint on American culture, but the mix of merchandizing and music making that characterized the Ford inspired, fiddle mania influenced the young Earl Latta in unmistakable ways. Like Henry Ford, Latta would use the platform and resources afforded by successful business ventures to shape the music and culture of Southwest Tennessee in ways that are apparent even now. Part III of this series will detail the legacy of Earl Latta’s famous garage jams at Latta Ford Motors in downtown Selmer, Tennessee. A fuller discussion of Latta’s role in West Tennessee music history was published in my essay, Everybody Who’s Anybody: Making Music for Earl Latta and Stanton Littlejohn, Volume LXXI, Numbers 1 & 2 (double issue) of the Tennessee Folklore Society Bulletin. The four part series, Fords & Fiddles, appears as a guest column by Shawn Pitts in the March 2023 issues of The McNairy County News and on Pitts's blog, Broomcorn, with additional links and photos.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

|

|

Photo credits: Huffoto (Arts in McNairy's official photographer)

|

Arts in McNairy | 205 W Court Ave, Selmer, TN | PO Box 66, Selmer, TN 38375 | 731-435-3288| [email protected]

RSS Feed

RSS Feed