|

In 2022-23 Arts in McNairy was a local study partner for Arts in Economic Prosperity 6 (AEP6), a nationwide survey of arts organizations, audiences. and patrons of the arts. The study measured economic impact of nonprofit arts agencies on the communities they serve. Responses from event attendees were also gathered to reveal local attitudes about arts programs and the organizations who present them. Not surprisingly, the individualized report for McNairy County showed tremendous economic impact by Arts in McNairy and other local arts partners. Arts programs created jobs and income for local families, retained and generated new tax revenues and enhanced cultural tourism. Key economic impact takeaways were:

Locals and visitors alike reported placing a great sense of value and high levels of satisfaction with the community arts programs they attended. Those polled largely agreed that:

The report conclusively proves that Arts in McNairy and the artists supported by the organization's programs substantially contribute to community livability and are major players in the region's economic vitality. The full, detailed AEP6 report of findings may be viewed at the AFTA website here.

0 Comments

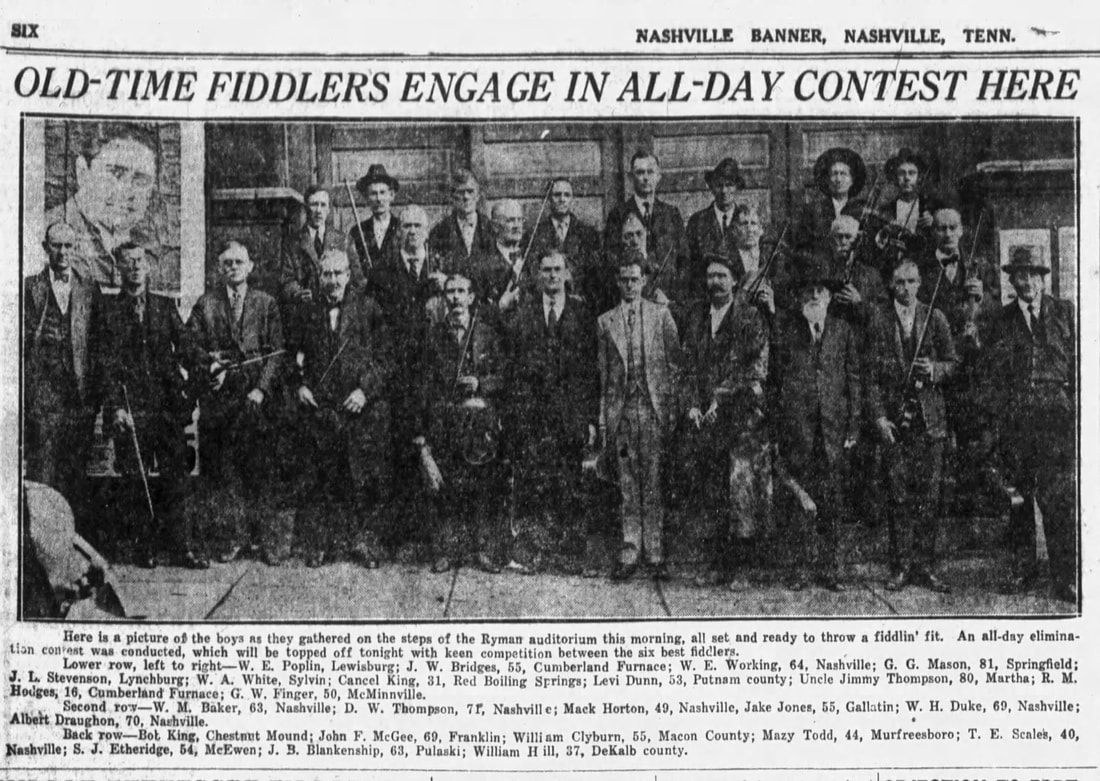

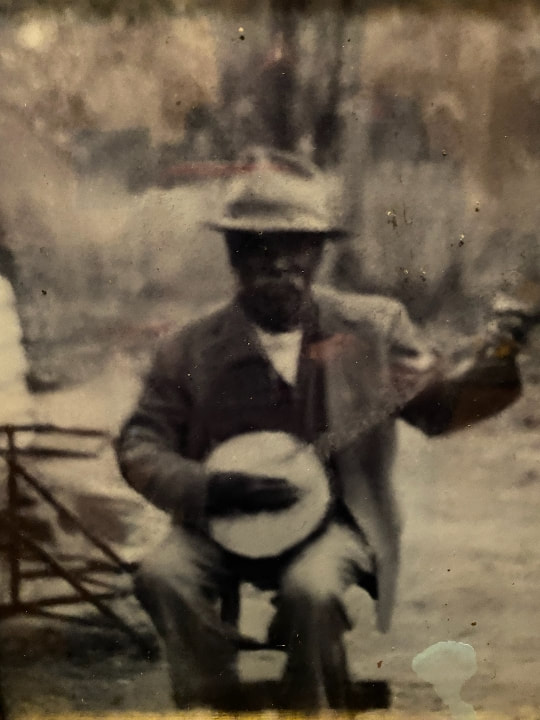

Left: The famous hubcap in the Latta Theater is a nod to the space's former life as Ford auto garage. Right: The large oil and acrylic painting, "Quite the Thing," by artist Lanessa Miller, was created at the Latta during her six week residency there. Inspired by the property's history and deep roots in local music culture, the artist depicted a typical weekend jamboree (Circa 1950) at the Latta Ford Motor Company, donating the work to Arts in McNairy at the conclusion of the residency. The painting now hangs in the south theater entrance as another reminder of the creativity of generations past. The hubcap goes largely unnoticed, but occasionally someone asks about it. For people who don’t know the history of the Latta building, it probably does seem somewhat incongruous; an old hubcap stuck in the wall of a beautifully appointed community theater and concert venue. It’s positioned high on a brick column near the stage, where it has acted as silent sentinel, watching over hundreds of performances of every variety for more than a decade now. It was not always so. Before new life was breathed back into the place, the hubcap was witness to dereliction and decay. Mice and rats scurried across the garage floor when it wasn’t flooded, while birds came in through holes in the roof to nest in the Latta building’s steel girders. The thriving business where local men and women had spent entire careers; the showroom floor where folks had kicked the tires and dreamed of the day they could save money enough for that new Ford, and then bought it; the garage and makeshift concert hall where Elvis Black, and Waldo Davis, and Carl Perkins, and the Latta Ramblers had electrified grateful audiences with their music; that historic space sat empty and falling in on itself, a shell of its former glory, a bothersome eyesore in the shadow of the County courthouse. It took almost five years to recover and restore the former Latta Ford building. The process included consensus building, open public meetings and discussions, committed local leadership, countless hours of planning, and fruitful partnerships between a half dozen government and nonprofit agencies. It was worth every second and every cent. Arts in McNairy’s residency at the McNairy County Visitors and Cultural Center has been transformative for this community. It is, at once, an astounding mobilization of contemporary creative resources, and a respectful homage to the the traditional music and culture of generations past. Local creatives are again invited to publicly practice their art for appreciative audiences, while touring acts and exhibits provide quality entertainment and learning opportunities for locals, who would otherwise have to travel many miles for similar offerings. At the 2020 McNairy County Music Hall of Fame inductions, Arts in McNairy board member, Christy Sills remarked, “A whole new generation of McNairy County youth is familiar with the name Latta. When they hear the name, they are most likely to associate it with the property situated at the corner of West Court Avenue and North 4th Street in downtown Selmer. More precisely, they are likely to think of the cultural experiences they enjoyed at what is now affectionately referred to as “The Latta.” Sills went on to recount some of the history of the Latta Ford Motor Company building as a cultural space, noting that the hundreds of children and adults who come through the doors today, are heirs to an incredible legacy of creative community building, renewed in their generation by Arts in McNairy’s dedicated volunteers. I could not agree more. When I walk in the Latta to find dozens of proud parents, grandparents and student artists lingering in the gallery at a youth art exhibit, I can’t help thinking of the shiny Fords that once graced those colorful tile floors. When I walk into a theater packed with wide-eyed school children, enthusiastically applauding the young cast of a local community theater production, or watch a bluegrass band take the stage, I can’t help thinking of Earl Latta. I’m convinced he would be deeply moved by the impact Arts in McNairy has made on the community he loved, and grateful that such programs are carried out in the majestic old building that still bears his name. Latta is, quite literally, etched in stone above the door. So, when some curious soul asks, “What’s with the hubcap?” I can’t wait to tell them the story. You can imagine how that goes; it’s taken me four installments to tell it to you here. But the way I figure it, you shouldn’t ask if you don’t want to know. I start by telling them that the hubcap was used to cover the open vent hole, when a wood burning stove was removed many years ago, and how the workmen scratched their heads in confusion when we insisted that it stay as a constant reminder of the building’s history. Sometimes the astute listener will ask me, “But what does a hubcap have to do with the history of a theater?” That’s when I know I’ve hooked them. And so I begin, “There was a young man named Earl Latta…” The four part series, Fords and Fiddles, appears as a guest column in the March 2023 issues of The McNairy County News. By 1937, Earl Latta was a well established businessman in Selmer, Tennessee. He had worked his way up from Ford mechanic to Ford dealer, purchasing the local franchise and rebranding it Latta Ford Motor Company. With Latta’s natural entrepreneurial skills and the growing popularity of Ford’s affordable products, the dealership rapidly became one of the best small-town franchises in the region. The Court Avenue location in the middle of downtown was a good one—just a block from the county courthouse and a half block from the Gulf Mobile and Ohio Railroad tracks—but space soon became a concern. In 1937 Latta broke ground on a new building with a spacious showroom, business offices, large drive-in garage, separate oil and wash bays, and all the amenities of the day. The building’s handsome brick exterior had art deco lines, medallions, and other decorative details. A colorful broken tile mosaic graced the floor of the showroom and of other public areas. “Latta” was boldly carved in stone above the main entrance. It was easily the nicest building in town, if not the county. Only the courthouse, just across the street, could rival it for small town architectural grandeur. Just as significant as the structure and business which operated there were the social dimensions the building would assume in years to come. Considering the gregarious nature of the owner, it was perhaps inevitable that the spacious new building, with its proximity to the courthouse and the downtown shopping district, would become something of a gathering place. Two generations of area residents fondly recalled dropping in at the Ford place to catch up on the latest gossip, enjoy an ice cold Coca Cola from the cooler, or just shelter from the weather. Rather than regarding this as a nuisance, Earl Latta welcomed, and even encouraged, such activities as an act of simple hospitality. He enjoyed people and was generous almost to a fault; the community loved him for it. It wasn’t too bad for business either. Latta was an extremely successful Ford dealer for more than forty years, reaping considerable financial rewards but always retaining the easy going manner of a farm boy. That human touch made him a popular and much beloved local figure. Once his business was established and flourishing at the new location, Earl Latta did the unexpected: he turned the garage area into a popular concert venue. He was undoubtedly influenced by the Henry Ford inspired old-time music trend that dated to the 1920s, but old-time music wasn’t a fad in McNairy County, Tennessee; it was a way of life. Latta had grown up in a community and family that surrounded him with music from birth. His mother was a dulcimer enthusiast, one brother was a fiddler, and another a banjo player. Earl was, himself, handy with both guitar and mandolin. Throughout his youth, the family actively participated, as both performers and hosts, in home “musicals” or “frolics,” as they were sometimes termed. In the first half of the twentieth century, frolics and community dances were a stable of entertainment in the South. McNairy County was hardly unique in that regard, but it was incredibly rich in old-time music and dance. Scheduled in one-room schoolhouses and other public spaces around the region—but as often as no, spontaneous gatherings in homes—these musical events followed the same basic format. Rugs were rolled up and furniture was removed to make way for eager musicians, revelers and spectators who played and danced, sometimes until the wee hours of the morning. The outbreak of World War II and the rise of mass media culture—especially the increasing availability of television—threatened to put an end to this type of live entertainment, but not in Selmer, Tennessee where the frolic took an unexpected turn into the realm of entertainment marketing. The wealth of the area’s musical talent and popularity of their shows and dances were not lost on the savvy Latta. By the mid to late 1940s the shrewd business owner had managed to combine his love of music and automobiles into an expanded version of the frolic at his spacious downtown garage. These regular events became a staple of community life, attracting some of the region’s best pickers and audiences numbering into the hundreds. Larger jams were intentionally scheduled to coincide with Ford’s new model year rollout so concertgoers could kick the tires and get a gander at the alluring chrome and shiny fenders strategically positioned on the Latta showroom floor. Earl Latta’s garage jams are the stuff of legend. For a decade or more, they offered a community without a formal concert hall a place to gather and socialize while some of the region’s top talented flexed their creative muscle on Latta’s makeshift stage. The house band, who styled themselves The Latta Ramblers, backed some of the best pickers southwest Tennessee had to offer, and were themselves among the region’s most respected musicians. Perhaps more important than the fleeting entertainment value, Earl Latta’s garage jamborees offered a hothouse environment where old-time pickers rubbed elbows with a new breed of musician. This arrangement preserved the region’s traditional music even as the generational cross-pollination helped transform it into what is now known as bluegrass, rockabilly and country. Indeed, a young Carl Perkins, among other influential West Tennseee figures, was known to frequent Latta’s legendary jams. Or as one attendee told me, “Everybody who’s anybody played for Earl Latta.” The final installment of Fords and Fiddles with take the reader inside the restoration of a derelict and deteriorating Latta Ford Motor Company building, and it’s transformation into a center for music and art; an outcome that would undoubtedly have made Earl Latta proud. A longer, more detailed, account of Earl Latta’s garage jamborees can be read in Everybody Who’s Anybody: Making Music for Earl Latta and Stanton Littlejohn, Volume LXXI, Numbers 1 & 2 (double issue) of the Tennessee Folklore Society Bulletin. The four part series, Fords & Fiddles, appears as a guest column by Shawn Pitts in the March 2023 issues of The McNairy County News and on Pitts's blog, Broomcorn, with additional links and photos.  The January 19, 1926 Nashville Banner covered the Ford sponsored Tennessee old-time fiddle contest finals. Some 25 fiddlers, primarily from Middle Tennessee, competed for the state title. Numbered among them were John L. “Uncle Bunt” Stephens (incorrectly identified here as J.L. Stevenson), Uncle Jimmy Thompson, and Marshall Claiborne (incorrectly identified here as William Clyburn). Stephens and Claiborne would play for Henry Ford later that year in Detroit, with Stephens claiming victory in the national fiddling finals which probably never took place. Thompson, the more seasoned and perhaps most talented musician of the group, was famed announcer, Judge George D. Hay’s, first guest on the Grand Ole Opry. Earl Latta was a Ford man, through and through.

Latta was born in the Gravel Hill community of McNairy County, Tennessee in 1895, just two years after Henry Ford produced his first automobile. The young Latta took a job at 18 years old, servicing Model T Fords at a garage in nearby Selmer. Intelligent, a born salesman, and enamored of the new advances in personal transportation, he quickly absorbed a good working knowledge of the new motorcars and the burgeoning American automobile industry. Henry Ford was a role model for the budding entrepreneur, and Latta followed the auto tycoon’s career with great interest. What he learned, coupled with what he already knew about West Tennessee music, would serve him well in the years to come. When Latta shipped out for active duty in France during World War I, he had never been more than a few miles from his boyhood home. After completing a tour of duty he returned to Gravel Hill where a disagreeable turn in farming was enough to convince the young man that agriculture was not in his future. He moved to Selmer and resumed his lifelong love affair with the automobile as an employee at the local Ford dealership. By 1926 Latta had saved enough money to purchase his own Model A Ford coupe. He must have been a dashing figure—a young man with money in his pocket motoring about a rural Tennessee town where mules and wagons were far more common. The same year Latta bought his first automobile, an old-time music craze was sweeping the country. Curiously, the car and the craze sprang from the same fertile imagination. In the mid 1920s, Henry Ford began systematically promoting old time dance and music events—especially fiddle contests—through his rapidly expanding network of automobile dealers. With the Roaring Twenties well underway, Ford felt the excesses of the Jazz Age were eroding the simpler times and wholesome entertainments of his youth. He mobilized local Ford dealers who sometimes partnered with booster clubs, civic groups, or fraternal organizations to host old-time fiddle contests as qualifying events, inviting the winners to compete for state and regional titles. The Volunteer State naturally produced a respectable crop of fiddlers including John “Uncle Bunt” Stephens, “Uncle” Jimmy Thompson, and the one-armed fiddling sensation Marshall Claiborne who took top honors at Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium. The three Tennesseans then competed in Louisville, Kentucky for the “Champion of Dixie” title with Stephens and Claiborne supposedly advancing to Detroit for the finals. After that, things get a little more fuzzy. Several fiddlers—Stephens among them—apparently did play for Henry Ford at a Detroit gathering of Ford executives and dealers, but there is no record of a fiddle contest taking place, let alone the crowning of a national champion. Stephens, whose yarn spinning rivaled his fiddling, told Nashville reporters that he attempted to bow out of the contest with the excuse that he’d only split enough wood to last his family three more days. He claimed Henry Ford dispatched one of his agents to Lynchburg to provision the Stephenses with wood and other necessities, set him up in a private room at the Ford estate, and bestowed on him the title of national old-time fiddle champion. What really happened in Detroit is unclear, but a good Southern tale relies more on the quality of the story than the facts, so Stephens’s humorous version of events persists in Tennessee music lore. McNairy County was not left out of the fun. An “Old Fiddler’s Contest,” sponsored by the Selmer Parent Teacher Association, took place on April 15, 1926. Though advertising for the event never mentioned the local Ford dealer, the contest undoubtedly grew out of the national enthusiasm for old-time music touched off by Henry Ford’s thinly veiled social agenda. A deep regional music tradition in Southwest Tennessee, and an incredibly strong crop of local fiddlers, certainly wouldn’t have hindered matters. The winners of the Selmer contest were apparently never published, but you can bet fiddlers such as Con Crotts, Elvis Black and Waldo Davis were in the running. It is impossible to know if Earl Latta was present for the McNairy County fiddle contest, but his longstanding affiliation with Ford, coupled with his personal affinity for old-time music, make it hard to imagine him sitting it out. The old-time music and dance craze left an indelible imprint on American culture, but the mix of merchandizing and music making that characterized the Ford inspired, fiddle mania influenced the young Earl Latta in unmistakable ways. Like Henry Ford, Latta would use the platform and resources afforded by successful business ventures to shape the music and culture of Southwest Tennessee in ways that are apparent even now. Part III of this series will detail the legacy of Earl Latta’s famous garage jams at Latta Ford Motors in downtown Selmer, Tennessee. A fuller discussion of Latta’s role in West Tennessee music history was published in my essay, Everybody Who’s Anybody: Making Music for Earl Latta and Stanton Littlejohn, Volume LXXI, Numbers 1 & 2 (double issue) of the Tennessee Folklore Society Bulletin. The four part series, Fords & Fiddles, appears as a guest column by Shawn Pitts in the March 2023 issues of The McNairy County News and on Pitts's blog, Broomcorn, with additional links and photos. In April 1931, a shiny, new Model A Ford rolled off the assembly line and into history. The stylish black Town Sedan was the twenty millionth automobile produced by Ford Motor Company, and they did not let the milestone pass without ceremony. Henry Ford, himself, stamped the serial number on the engine block and drove the car out of the plant as it embarked on a nationwide tour with Ford’s familiar blue oval logo and the words “The Twenty Millionth” emblazoned in large block letters down the sides and across the top.

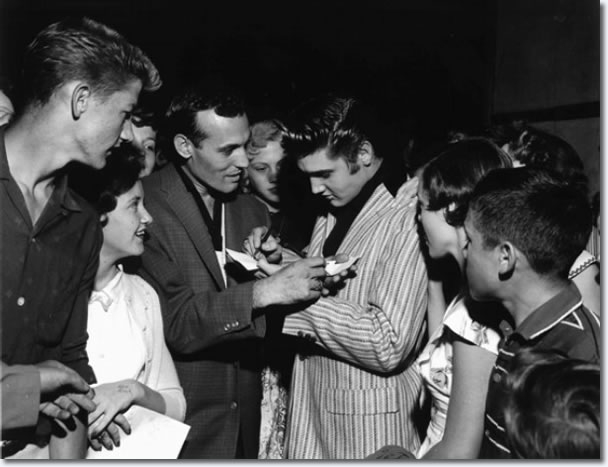

The Model A was joined by other vehicles in the Ford fleet as the promotional caravan rolled across the country, making scheduled stops at national monuments, scenic parks, statehouses, and countless small town Ford dealerships. The car was the star attraction at every stop; movie stars, politicians and other dignitaries clamored to pose with the vehicle or take it for a test drive at the invitation of tour organizers. Eleanor Roosevelt and Douglas Fairbanks among dozens of other celebrities were photographed behind the wheel at various ports of call. Police motorcades escorted the celebrity Model A into towns where brass bands heralded its arrival, and locals turned out by the thousands to see the spectacle. States issued one of a kind license plates numbered 20,000,000 to mark the occasion, presenting them to Ford representatives with great pomp and pride. The car even made a few laps and took the checkered flag at Indianapolis Motor Speedway, and became the first private vehicle to descend to the bottom of Hoover Dam for a photo op. It was a welcome season of levity; a brief respite for a nation in the throes of the Great Depression. With automobile sales slumping and Americans in desperate need of a morale boost, Ford could hardly have planned a better public relations campaign. Back in Detroit, the car remained a novelty item for a short time, but the world soon moved on. For many years, the original twenty millionth Model A was presumed to have been destroyed in a fire, along with the registry book logging the tour stops, commemorative state plates, and other souvenirs picked up along the way. But in the 1990s the car was almost miraculously rediscovered in storage, still owned by the family who purchased it from Ford in 1940. The deteriorating sedan underwent a total restoration in the early 2000s to bring it back to pristine, original condition in honor of Ford’s 2003 centennial celebration. The company then leased it for ten years to be displayed at their world headquarters in Dearborn, Michigan. Though the log book and commemorative plates from the national tour have never been found, hundreds of photos documenting the famous Model A’s triumphant, cross-country journey have resurfaced to document that moment in time. Imagine my surprise when one such photograph turned up while I was researching the history of Latta Ford in Selmer. The photo shows a group of McNairy County dignitaries gathered around the Twenty Millionth Ford outside the local dealership. It was taken shortly before Earl Latta purchased the business and broke ground on a new location, 205 West Court Avenue, at what is now the McNairy County Visitor’s and Cultural Center. When the photo was taken, the local dealership, Bolton Ford, was in the 100 block of West Court Avenue, where present day China King is located. This image came to light more than a decade ago, thanks to Nancy Kennedy at the McNairy County Archives. As a young woman, Nancy worked for Earl Latta, so she was always keen to preserve anything related to the history of his successful business ventures. The photo appears to be copied from newsprint with a 1932 date, supplied by an unknown archivist. In all likelihood, that date is one year off, given that the tour concluded in December 1931, and can be documented in Middle and East Tennessee, as early as June of the same year. Inaccurate date or not, it’s a wonderfully evocative photo tying local people to a an historic event of national significance. Part two of this essay will detail how Henry Ford may have inspired a young Earl Latta to indulge his interest in old-time music while refining his sales pitch for Ford motorcars. The four part series, Fords & Fiddles, appears as a guest column by Shawn Pitts in the March 2023 issues of The McNairy County News and on Pitts's blog, Broomcorn with additional links and photos. Bethel Springs, Tennessee--Once you know The King of Rock ’n’ Roll performed one of the first concerts of his illustrious career in your tiny hometown, what do you do with that? The people at Bethel Springs, Tennessee have an idea or two. It is a well established fact that Elvis Presley played to a young audience at Bethel Spring School in the days immediately following the release of his first single on Memphis-based Sun Records. Presley recorded his first hit single, That’s Alright (Mama)/Blue Moon of Kentucky, at Sun in July 1954. The record was getting good airplay on regional radio, and Presley’s, now famous, performing style was receiving plenty of media attention, both positive and negative. His management felt it was time Presley got out of Memphis to promote the record and connect with his growing fandom. They booked him in places where an up and coming young talent could cut his teeth as a performer, and maybe make a few new converts for his infectious new sound. Bethel Springs was one such place. Fast forward almost 70 years and you have the rise and untimely demise of The King of Rock ’n’ Roll in the rearview mirror, and the small town of Bethel Springs making plans to commemorate an event that marked a significant launching pad for Elvis Presley’s stratospheric rise to superstardom. “We just knew this concert was an historic event that happened in our community,” said Patricia Huggins, “but not much has been done to call attention to it.” Huggins and Judith Olson, two Bethel Springs natives, are numbered among a small group of locals who are trying to change that as part of McNairy County’s 2023 bicentennial celebration. The dedicated group quickly found important allies in a team of researchers working with Arts in McNairy. By sheer coincidence, Arts in McNairy has recently undertaken an ambitious program to document various features of the county’s cultural history. The study just happened to coincide with the Bethel Springs group’s desire to memorialize the Presley concert in their town. When Huggins and Olson contacted AiM representatives to inquire about resources, a partnership and plan quickly came together. The combined group will hold a meeting, 1:00 p.m. February 25th at Bethel Springs City Hall. The team will be interviewing those who were eye witness to the Presley concert and others who may have corroborating information, in a fun and informal setting. Artifacts, personal accounts, and remembrances are being sought to offer ironclad documentation that will assist the Bethel Springs group in planning for a bicentennial commemoration. Initial discussions revolve around installation of an historical marker and perhaps a public ceremony of some kind. “We’ve always known this was a significant performance in Elvis’s career,” Olson explained, “but we would like his fans, the world over, to know it too.” Anyone with helpful information is invited to attend the upcoming meeting. Arts in McNairy may be contacted at: [email protected] or (731) 435-3288, for questions about the session, or to provide information and promising leads about the Presley concert at Bethel Springs. Information may also be exchanged by using the comments section below. Exploring local culture has long been a priority for Arts in McNairy. The county arts agency made its first foray into the region’s traditional arts in 2006, completing a two year study that revealed a deep well of untold or forgotten stories about McNairy County’s creative heritage.

“It’s about more than just gathering information,” said Shawn Pitts, Arts in McNairy’s Traditional Arts Chair. “We realized that we had to give these stories back to the public in a way that helped community members grasp their significance. Maybe more than that, we wanted people to take pride in the county’s creative accomplishments.” Fortunately, AiM leadership found many ways to accomplish that goal. The AiM Artisan Trail brought attention to the area’s many quality craftspeople; the Rockabilly Highway Mural initiative and McNairy County Music Hall of Fame created awareness about the county’s music history; and the McNairy County Visitor’s and Cultural Center grew, in part, out of the desire to preserve the Latta building’s history as a cultural space. It’s hard to overestimate the attention these efforts have brought to McNairy County’s rich history of art and music making, but AiM representatives say the work is never really complete. “There’s always more to learn,” Pitts said. “We’ve been discussing an updated survey for several years now, but with the county’s bicentennial upon us, 2023 seemed like the right time.” Beginning in January 2023, Pitts and LaShell Moore, the organization’s Diversity Chair, will undertake a yearlong study focused on the county’s African American, Native American and Hispanic traditions. The team also hopes to explore recent immigrant cultures, as time and resources permit. “We want to cast the net as broadly as possible,” said Moore. “It’s important to reach communities that may have been missed in the last study.” The study will involve guiding community members through survey questions, taking oral histories and collecting information about the contemporary and traditional creative pursuits of McNairy County residents. The survey team is searching for two young interns, ages 17-25, to assist with the work. They say youthful enthusiasm will bring energy to the project, but the team hopes to inspire young community members with the stories collected in the process. Those interested may apply for the paid internship online. Question should be directed to: [email protected] or call (731) 435-3288. The new cultural study begins in January 2023 and is expected to last 8-12 months. Results will be published in various forms as information is collected and analyzed. The creative mind behind the two iconic murals in downtown Selmer, Tennessee will return to McNairy County for a command performance. Nashville artist, Brian Tull, was recently commissioned to complete a third mural, the latest in a public art initiative that began over a decade ago with Tull’s Rockabilly Highway Mural. That was the first public art project for both Tull, and the county art agency, Arts in McNairy, but it wouldn’t be the last.

Tull, a working studio artist, has since established himself as a sought-after muralist, creating ambitious public art projects in Chicago, North Carolina, Mississippi and his adopted hometown, Nashville. Originally from Selmer, Tull returned home for a second Rockabilly Highway Mural in 2012, and the results have been transformative for his hometown “When Brian came on board for the first mural,” said Dr. Shawn Pitts, AiM Board member and project cochair, “there wasn’t a lot going on in downtown. With the addition of Rockabilly Highway Murals I and II, we’ve seen steady retail growth in the town’s traditional business district as well as tremendous interest from cultural tourists both domestic and international. That’s a direct result of Brian’s artistic vision, and a big win for McNairy County.” Beyond the economic impact of the murals, many observers have noted a shift in local attitudes. Arts in McNairy leadership envisioned the initiative as positive representations of the area’s rich music culture which could educate and engender pride of place. “I don’t think people really understood the significance of this region’s music heritage until those murals went up,” said downtown photographer and business owner, Bryan Huff. “Now residents have a better sense of that history and a good reason to be proud of it. I’m glad to see the project continuing.” The new mural will be installed over the coming months and dedicated at the 2023 Rockabilly Highway Revival next June. Thanks to the generous cooperation of longtime downtown business owner, Peggy Griffin, the location will be the southwest facing wall of Tru Savers Hardware. It’s a high visibility location, adjacent to the county courthouse, just across South 3rd Street from the U.S. Postoffice. The project will be funded, in part, by a Tennessee Arts Commission grant. Progress on the mural may be followed on this website or Arts in McNairy's Facebook and Instagram pages. Supporters can help defray the costs by donating to the project’s GoFundMe page. By Shawn Pitts

It has been my great honor to write a series of articles for the Independent Appeal on the occasions of Arts in McNairy’s twentieth anniversary. Conference organizers have often invited me to offer reflections on the unlikely success of a nonprofit arts agency in a rural county like McNairy, but I rarely get to share those insights here at home. I thought a few observations on the subject would be a fitting way to bring these guest columns to a close. One reason I am frequently asked to talk about Arts in McNairy’s success over the past two decades is its rarity. The speaking and writing invitations that come my way are almost exclusively directed toward assisting other rural arts developers identify and avoid common pitfalls and make the most of the cultural opportunities unique to their communities. Arts in McNairy didn’t necessarily crack the code on rural arts development but I believe there are a number of reasons the organization succeeded where others became frustrated and threw in the towel. Here are my top three: Community Focus—If I had to pick one thing that sets AiM apart, it would be the unflinching efforts of the organization’s leadership to maintain focus on the community. That’s not as simple as it may sound. Many nonprofits devolve over time to serve their own narrow interests, but focusing internally rather than externally, is the kiss of death for organizations who purport to serve the community. Those who support AiM can rest assured that every dollar spent, every decision made, every volunteer mobilized is in the interest of making the arts an integral part of life in McNairy County. One of the organization’s founding principles is that a community is only healthy when opportunities for all citizens to participate in the arts abound. I was on a conference panel with former County Mayor, Jai Templeton, several years ago when he was asked to share his perspective on AiM’s success. I deeply appreciated his response. “Arts in McNairy is not a one issue organization,” he observed. He clarified by commending AiM for its broad community involvement and partnerships with local government and other area nonprofits. AiM’s primary mission was always about the arts, but Jai recognized the organization’s emphasis on collaborating to create a more engaged community on every front. Accessibility, Diversity and Inclusion—Very early in the organization’s development it was acknowledged that creativity, in all its forms, should be respected and included in programming. It is the right thing to do, but it also helped the program committees reach underserved audiences and bring in voices and art forms that might have been neglected otherwise. Where many rural arts agencies concern themselves with a single discipline (painting, theatre, etc.) AiM functions as an umbrella arts agency offering programs in an ever-broadening variety of creative endeavor. You would be hard pressed to find many arts agencies in the rural South who have presented community programs in, music, visual arts, literature, theatre, dance, puppetry, digital media, film, folklife, culinary arts, creative writing, arts education, cultural history, spoken word, and more. Similarly, as the organization has grown and evolved, the leadership has constantly sought to widen its reach to ensure that all community members are represented in programming and decision making, regardless of race, age, ability or socioeconomic status. The arts are for everyone, and a dedicated committee now advises the AiM board on issues of inclusion, access and diversity. Commitment to the Cause—Space would not permit me to name the hundreds of committed individuals who have contributed their time, expertise, and resources to make Arts in McNairy a success over the years. From the first meetings held to gage interest in forming a local arts agency in 2000 and 2001, it was apparent that the community was hungry for new cultural programs, and we have never been without artists, leaders, volunteers, donors and enthusiastic audiences to make them happen. Some may have doubted that McNairy County was capable of developing and sustaining a vibrant creative community, but they severely underestimated the commitment of their neighbors to cultivate a welcoming environment for the arts and artists of every variety. We owe a debt of gratitude to a community that embraced the AiM mission from the outset, especially those who rolled up their sleeves and went to work for a cause larger than themselves. It has paid off ten times over. I sometimes hear people say nothing ever changes in McNairy County, but they are dead wrong, and I am tired of hearing that stale, old mantra. It’s insulting to people who’ve worked tirelessly to make positive impact on our community and I immediately tune out anyone regurgitating that false claim. I could cite AiM accomplishments and brag on the people who made them possible for another ten columns without scratching the surface. I could tell many stories about how the arts have positively impacted lives and transformed the futures of local students. I could give hard data and statistics showing improved economic conditions attributable to sustained community cultural development. I could line up witnesses around the block who would gladly confirm every detail. But if there’s one thing I’ve learned in twenty years of community building, it’s this: you can’t solve a problem for people in love with the problem and you’ll only burn yourself out trying. Arts in McNairy has had an incredible, historic run over the past two decades and I could not be more proud of this community and the individuals, businesses and elected officials who saw the potential in a grassroots movement to build creative community and possessed the foresight and resolve to see it through. This is a better community than it was twenty years ago and I expect even greater things over the course of the next twenty years. Trust me when I say, the arts are here to stay. This post originally appeared in the McNairy County Independent Appeal By Shawn Pitts

I was grateful that the Independent Appeal ran a Discover McNairy column on the Tennessee music box a few weeks ago. It is a fascinating history and the article covered the details of how ten of those instruments were rediscovered and came to be in the possession of Arts in McNairy, so I won’t rehash those points. But people often wonder why a local arts agency would expend so much time and effort rounding up crudely made instruments that resemble packing crates more than their glamorous sisters, the mountain dulcimer. It’s a good question. I sometimes call it attic archaeology since most of the known Tennessee music boxes have been discovered in sweltering attics, dank basements and dusty haylofts. Many more never survived such harsh conditions and others were thrown out with the trash because people didn’t know, or care, what they were. That makes the urgent pursuit and recovery of these scarce folk instruments a lot like archaeology, only with digging through castoff junk in old attics instead of digging in the earth for lost civilizations. In the end, the goal is much the same: to learn what the artifacts can teach us about the people who made and used them. In the case of the Tennessee music box, we are talking about the rural people who inhabited southwest and south middle Tennessee from Reconstruction until about World War II. The fine details of the construction reveal much about the ingenuity of our forbearers. The rare music boxes—a form of box dulcimer—were never commercially produced. Each instrument was lovingly constructed by a craftsman from materials on hand. The bodies and fretboards are typically made of rough poplar planks. Snuff cans, tobacco tins, hinge pins, fences stables and other readily available items were often used to form the metal bridges, nuts and frets. The four tuning pegs were commonly made of eye screws. Ornamentation included recessed mother of pearl buttons, hand painted finishes, and sometimes carving on the top or along the fretboard. Creative configuration of the tone holes also contribute to the unique aesthetic character of each instrument. One music box has the faint remains of a checkerboard painted on the back. It was apparently flipped over on occasion to do double duty as a game table. Close examination of the wear patterns on the music boxes show that they were played in a variety of ways. Some instruments have the residue of rosin on the fretboard; evidence that they were bowed like a fiddle. Turkey feathers, homemade picks and noters discovered with the instruments or sometimes in their hollow bodies show that others were strummed. It is known that some players used a pocket knife, bottleneck or short piece of copper pipe to produce a slide effect similar to a dobro or blues and Hawaiian guitar styles. No one learned any of these techniques at conservatory or from a professional instruction manual; the remarkable variety of voices given to these versatile folk instruments were developed and passed along in community and family groups. Several have a direct connection to McNairy County, which was ground zero for Tennessee music box making. That they exist at all may be the most amazing thing about Tennessee music boxes. I don’t just mean that individuals like Ellis Truett Jr. and organizations like Arts in McNairy have shown an interest in their preservation. That’s a significant part of their story, but the mysterious, do-it-yourself origins of these instruments in the communities of the lower Tennessee River Valley speak to the universal human desire to create music. When there were no nearby music stores or family finances put expensive musical instruments beyond their reach, the rural people of our region turned to their own imaginations to develop their own kind of music. Arts in McNairy’s traditional arts committee believes that is an accomplishment worth remembering and celebrating. This post originally appeared in the McNairy County Independent Appeal |

|

|

Photo credits: Huffoto (Arts in McNairy's official photographer)

|

Arts in McNairy | 205 W Court Ave, Selmer, TN | PO Box 66, Selmer, TN 38375 | 731-435-3288| [email protected]

RSS Feed

RSS Feed