Left: The famous hubcap in the Latta Theater is a nod to the space's former life as Ford auto garage. Right: The large oil and acrylic painting, "Quite the Thing," by artist Lanessa Miller, was created at the Latta during her six week residency there. Inspired by the property's history and deep roots in local music culture, the artist depicted a typical weekend jamboree (Circa 1950) at the Latta Ford Motor Company, donating the work to Arts in McNairy at the conclusion of the residency. The painting now hangs in the south theater entrance as another reminder of the creativity of generations past. The hubcap goes largely unnoticed, but occasionally someone asks about it. For people who don’t know the history of the Latta building, it probably does seem somewhat incongruous; an old hubcap stuck in the wall of a beautifully appointed community theater and concert venue. It’s positioned high on a brick column near the stage, where it has acted as silent sentinel, watching over hundreds of performances of every variety for more than a decade now. It was not always so. Before new life was breathed back into the place, the hubcap was witness to dereliction and decay. Mice and rats scurried across the garage floor when it wasn’t flooded, while birds came in through holes in the roof to nest in the Latta building’s steel girders. The thriving business where local men and women had spent entire careers; the showroom floor where folks had kicked the tires and dreamed of the day they could save money enough for that new Ford, and then bought it; the garage and makeshift concert hall where Elvis Black, and Waldo Davis, and Carl Perkins, and the Latta Ramblers had electrified grateful audiences with their music; that historic space sat empty and falling in on itself, a shell of its former glory, a bothersome eyesore in the shadow of the County courthouse. It took almost five years to recover and restore the former Latta Ford building. The process included consensus building, open public meetings and discussions, committed local leadership, countless hours of planning, and fruitful partnerships between a half dozen government and nonprofit agencies. It was worth every second and every cent. Arts in McNairy’s residency at the McNairy County Visitors and Cultural Center has been transformative for this community. It is, at once, an astounding mobilization of contemporary creative resources, and a respectful homage to the the traditional music and culture of generations past. Local creatives are again invited to publicly practice their art for appreciative audiences, while touring acts and exhibits provide quality entertainment and learning opportunities for locals, who would otherwise have to travel many miles for similar offerings. At the 2020 McNairy County Music Hall of Fame inductions, Arts in McNairy board member, Christy Sills remarked, “A whole new generation of McNairy County youth is familiar with the name Latta. When they hear the name, they are most likely to associate it with the property situated at the corner of West Court Avenue and North 4th Street in downtown Selmer. More precisely, they are likely to think of the cultural experiences they enjoyed at what is now affectionately referred to as “The Latta.” Sills went on to recount some of the history of the Latta Ford Motor Company building as a cultural space, noting that the hundreds of children and adults who come through the doors today, are heirs to an incredible legacy of creative community building, renewed in their generation by Arts in McNairy’s dedicated volunteers. I could not agree more. When I walk in the Latta to find dozens of proud parents, grandparents and student artists lingering in the gallery at a youth art exhibit, I can’t help thinking of the shiny Fords that once graced those colorful tile floors. When I walk into a theater packed with wide-eyed school children, enthusiastically applauding the young cast of a local community theater production, or watch a bluegrass band take the stage, I can’t help thinking of Earl Latta. I’m convinced he would be deeply moved by the impact Arts in McNairy has made on the community he loved, and grateful that such programs are carried out in the majestic old building that still bears his name. Latta is, quite literally, etched in stone above the door. So, when some curious soul asks, “What’s with the hubcap?” I can’t wait to tell them the story. You can imagine how that goes; it’s taken me four installments to tell it to you here. But the way I figure it, you shouldn’t ask if you don’t want to know. I start by telling them that the hubcap was used to cover the open vent hole, when a wood burning stove was removed many years ago, and how the workmen scratched their heads in confusion when we insisted that it stay as a constant reminder of the building’s history. Sometimes the astute listener will ask me, “But what does a hubcap have to do with the history of a theater?” That’s when I know I’ve hooked them. And so I begin, “There was a young man named Earl Latta…” The four part series, Fords and Fiddles, appears as a guest column in the March 2023 issues of The McNairy County News.

0 Comments

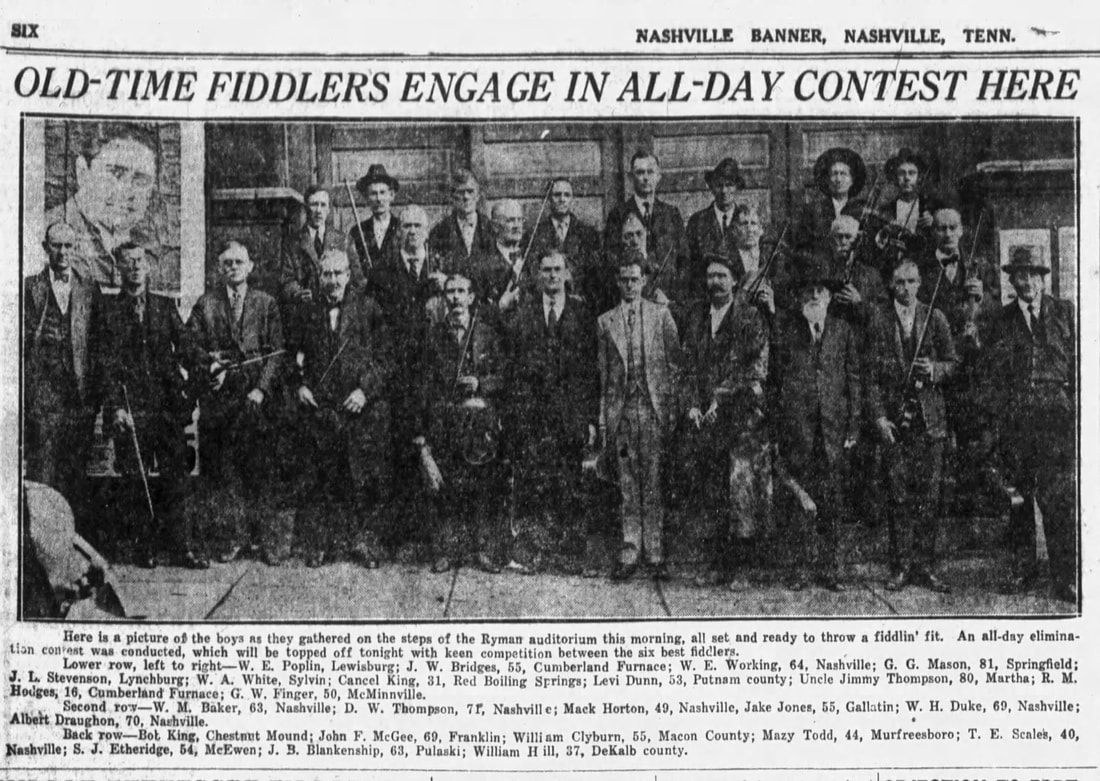

By 1937, Earl Latta was a well established businessman in Selmer, Tennessee. He had worked his way up from Ford mechanic to Ford dealer, purchasing the local franchise and rebranding it Latta Ford Motor Company. With Latta’s natural entrepreneurial skills and the growing popularity of Ford’s affordable products, the dealership rapidly became one of the best small-town franchises in the region. The Court Avenue location in the middle of downtown was a good one—just a block from the county courthouse and a half block from the Gulf Mobile and Ohio Railroad tracks—but space soon became a concern. In 1937 Latta broke ground on a new building with a spacious showroom, business offices, large drive-in garage, separate oil and wash bays, and all the amenities of the day. The building’s handsome brick exterior had art deco lines, medallions, and other decorative details. A colorful broken tile mosaic graced the floor of the showroom and of other public areas. “Latta” was boldly carved in stone above the main entrance. It was easily the nicest building in town, if not the county. Only the courthouse, just across the street, could rival it for small town architectural grandeur. Just as significant as the structure and business which operated there were the social dimensions the building would assume in years to come. Considering the gregarious nature of the owner, it was perhaps inevitable that the spacious new building, with its proximity to the courthouse and the downtown shopping district, would become something of a gathering place. Two generations of area residents fondly recalled dropping in at the Ford place to catch up on the latest gossip, enjoy an ice cold Coca Cola from the cooler, or just shelter from the weather. Rather than regarding this as a nuisance, Earl Latta welcomed, and even encouraged, such activities as an act of simple hospitality. He enjoyed people and was generous almost to a fault; the community loved him for it. It wasn’t too bad for business either. Latta was an extremely successful Ford dealer for more than forty years, reaping considerable financial rewards but always retaining the easy going manner of a farm boy. That human touch made him a popular and much beloved local figure. Once his business was established and flourishing at the new location, Earl Latta did the unexpected: he turned the garage area into a popular concert venue. He was undoubtedly influenced by the Henry Ford inspired old-time music trend that dated to the 1920s, but old-time music wasn’t a fad in McNairy County, Tennessee; it was a way of life. Latta had grown up in a community and family that surrounded him with music from birth. His mother was a dulcimer enthusiast, one brother was a fiddler, and another a banjo player. Earl was, himself, handy with both guitar and mandolin. Throughout his youth, the family actively participated, as both performers and hosts, in home “musicals” or “frolics,” as they were sometimes termed. In the first half of the twentieth century, frolics and community dances were a stable of entertainment in the South. McNairy County was hardly unique in that regard, but it was incredibly rich in old-time music and dance. Scheduled in one-room schoolhouses and other public spaces around the region—but as often as no, spontaneous gatherings in homes—these musical events followed the same basic format. Rugs were rolled up and furniture was removed to make way for eager musicians, revelers and spectators who played and danced, sometimes until the wee hours of the morning. The outbreak of World War II and the rise of mass media culture—especially the increasing availability of television—threatened to put an end to this type of live entertainment, but not in Selmer, Tennessee where the frolic took an unexpected turn into the realm of entertainment marketing. The wealth of the area’s musical talent and popularity of their shows and dances were not lost on the savvy Latta. By the mid to late 1940s the shrewd business owner had managed to combine his love of music and automobiles into an expanded version of the frolic at his spacious downtown garage. These regular events became a staple of community life, attracting some of the region’s best pickers and audiences numbering into the hundreds. Larger jams were intentionally scheduled to coincide with Ford’s new model year rollout so concertgoers could kick the tires and get a gander at the alluring chrome and shiny fenders strategically positioned on the Latta showroom floor. Earl Latta’s garage jams are the stuff of legend. For a decade or more, they offered a community without a formal concert hall a place to gather and socialize while some of the region’s top talented flexed their creative muscle on Latta’s makeshift stage. The house band, who styled themselves The Latta Ramblers, backed some of the best pickers southwest Tennessee had to offer, and were themselves among the region’s most respected musicians. Perhaps more important than the fleeting entertainment value, Earl Latta’s garage jamborees offered a hothouse environment where old-time pickers rubbed elbows with a new breed of musician. This arrangement preserved the region’s traditional music even as the generational cross-pollination helped transform it into what is now known as bluegrass, rockabilly and country. Indeed, a young Carl Perkins, among other influential West Tennseee figures, was known to frequent Latta’s legendary jams. Or as one attendee told me, “Everybody who’s anybody played for Earl Latta.” The final installment of Fords and Fiddles with take the reader inside the restoration of a derelict and deteriorating Latta Ford Motor Company building, and it’s transformation into a center for music and art; an outcome that would undoubtedly have made Earl Latta proud. A longer, more detailed, account of Earl Latta’s garage jamborees can be read in Everybody Who’s Anybody: Making Music for Earl Latta and Stanton Littlejohn, Volume LXXI, Numbers 1 & 2 (double issue) of the Tennessee Folklore Society Bulletin. The four part series, Fords & Fiddles, appears as a guest column by Shawn Pitts in the March 2023 issues of The McNairy County News and on Pitts's blog, Broomcorn, with additional links and photos.  The January 19, 1926 Nashville Banner covered the Ford sponsored Tennessee old-time fiddle contest finals. Some 25 fiddlers, primarily from Middle Tennessee, competed for the state title. Numbered among them were John L. “Uncle Bunt” Stephens (incorrectly identified here as J.L. Stevenson), Uncle Jimmy Thompson, and Marshall Claiborne (incorrectly identified here as William Clyburn). Stephens and Claiborne would play for Henry Ford later that year in Detroit, with Stephens claiming victory in the national fiddling finals which probably never took place. Thompson, the more seasoned and perhaps most talented musician of the group, was famed announcer, Judge George D. Hay’s, first guest on the Grand Ole Opry. Earl Latta was a Ford man, through and through.

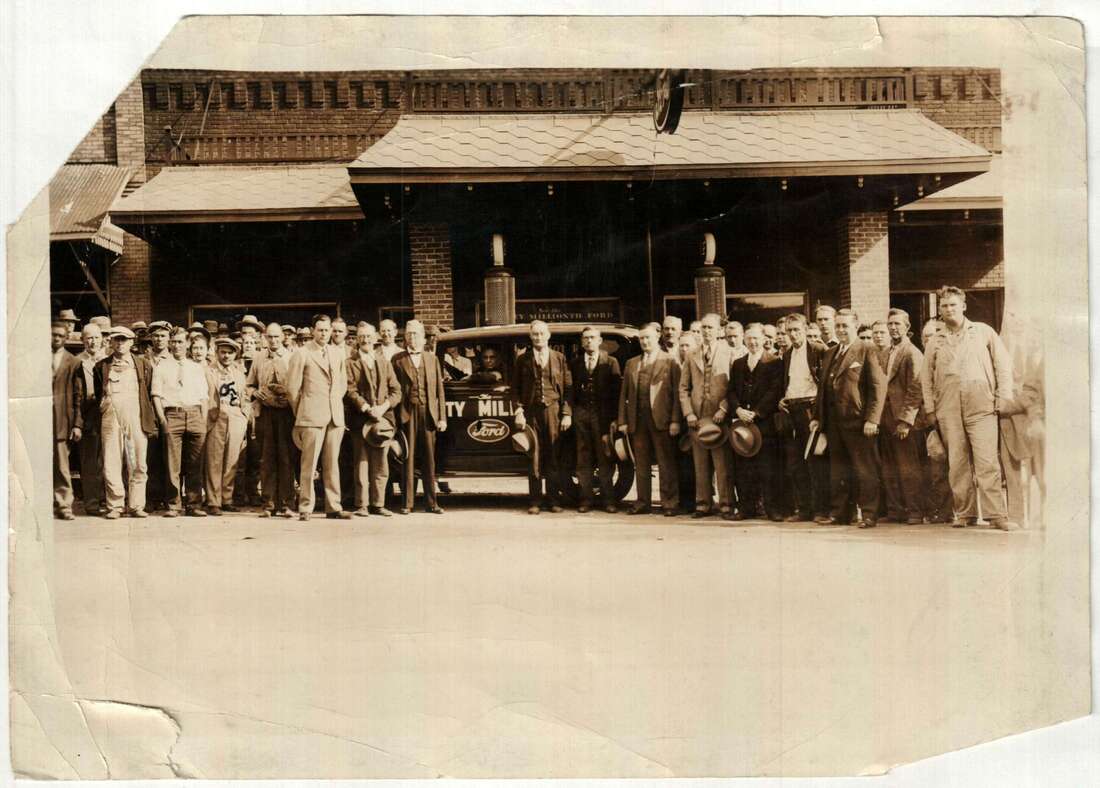

Latta was born in the Gravel Hill community of McNairy County, Tennessee in 1895, just two years after Henry Ford produced his first automobile. The young Latta took a job at 18 years old, servicing Model T Fords at a garage in nearby Selmer. Intelligent, a born salesman, and enamored of the new advances in personal transportation, he quickly absorbed a good working knowledge of the new motorcars and the burgeoning American automobile industry. Henry Ford was a role model for the budding entrepreneur, and Latta followed the auto tycoon’s career with great interest. What he learned, coupled with what he already knew about West Tennessee music, would serve him well in the years to come. When Latta shipped out for active duty in France during World War I, he had never been more than a few miles from his boyhood home. After completing a tour of duty he returned to Gravel Hill where a disagreeable turn in farming was enough to convince the young man that agriculture was not in his future. He moved to Selmer and resumed his lifelong love affair with the automobile as an employee at the local Ford dealership. By 1926 Latta had saved enough money to purchase his own Model A Ford coupe. He must have been a dashing figure—a young man with money in his pocket motoring about a rural Tennessee town where mules and wagons were far more common. The same year Latta bought his first automobile, an old-time music craze was sweeping the country. Curiously, the car and the craze sprang from the same fertile imagination. In the mid 1920s, Henry Ford began systematically promoting old time dance and music events—especially fiddle contests—through his rapidly expanding network of automobile dealers. With the Roaring Twenties well underway, Ford felt the excesses of the Jazz Age were eroding the simpler times and wholesome entertainments of his youth. He mobilized local Ford dealers who sometimes partnered with booster clubs, civic groups, or fraternal organizations to host old-time fiddle contests as qualifying events, inviting the winners to compete for state and regional titles. The Volunteer State naturally produced a respectable crop of fiddlers including John “Uncle Bunt” Stephens, “Uncle” Jimmy Thompson, and the one-armed fiddling sensation Marshall Claiborne who took top honors at Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium. The three Tennesseans then competed in Louisville, Kentucky for the “Champion of Dixie” title with Stephens and Claiborne supposedly advancing to Detroit for the finals. After that, things get a little more fuzzy. Several fiddlers—Stephens among them—apparently did play for Henry Ford at a Detroit gathering of Ford executives and dealers, but there is no record of a fiddle contest taking place, let alone the crowning of a national champion. Stephens, whose yarn spinning rivaled his fiddling, told Nashville reporters that he attempted to bow out of the contest with the excuse that he’d only split enough wood to last his family three more days. He claimed Henry Ford dispatched one of his agents to Lynchburg to provision the Stephenses with wood and other necessities, set him up in a private room at the Ford estate, and bestowed on him the title of national old-time fiddle champion. What really happened in Detroit is unclear, but a good Southern tale relies more on the quality of the story than the facts, so Stephens’s humorous version of events persists in Tennessee music lore. McNairy County was not left out of the fun. An “Old Fiddler’s Contest,” sponsored by the Selmer Parent Teacher Association, took place on April 15, 1926. Though advertising for the event never mentioned the local Ford dealer, the contest undoubtedly grew out of the national enthusiasm for old-time music touched off by Henry Ford’s thinly veiled social agenda. A deep regional music tradition in Southwest Tennessee, and an incredibly strong crop of local fiddlers, certainly wouldn’t have hindered matters. The winners of the Selmer contest were apparently never published, but you can bet fiddlers such as Con Crotts, Elvis Black and Waldo Davis were in the running. It is impossible to know if Earl Latta was present for the McNairy County fiddle contest, but his longstanding affiliation with Ford, coupled with his personal affinity for old-time music, make it hard to imagine him sitting it out. The old-time music and dance craze left an indelible imprint on American culture, but the mix of merchandizing and music making that characterized the Ford inspired, fiddle mania influenced the young Earl Latta in unmistakable ways. Like Henry Ford, Latta would use the platform and resources afforded by successful business ventures to shape the music and culture of Southwest Tennessee in ways that are apparent even now. Part III of this series will detail the legacy of Earl Latta’s famous garage jams at Latta Ford Motors in downtown Selmer, Tennessee. A fuller discussion of Latta’s role in West Tennessee music history was published in my essay, Everybody Who’s Anybody: Making Music for Earl Latta and Stanton Littlejohn, Volume LXXI, Numbers 1 & 2 (double issue) of the Tennessee Folklore Society Bulletin. The four part series, Fords & Fiddles, appears as a guest column by Shawn Pitts in the March 2023 issues of The McNairy County News and on Pitts's blog, Broomcorn, with additional links and photos. In April 1931, a shiny, new Model A Ford rolled off the assembly line and into history. The stylish black Town Sedan was the twenty millionth automobile produced by Ford Motor Company, and they did not let the milestone pass without ceremony. Henry Ford, himself, stamped the serial number on the engine block and drove the car out of the plant as it embarked on a nationwide tour with Ford’s familiar blue oval logo and the words “The Twenty Millionth” emblazoned in large block letters down the sides and across the top.

The Model A was joined by other vehicles in the Ford fleet as the promotional caravan rolled across the country, making scheduled stops at national monuments, scenic parks, statehouses, and countless small town Ford dealerships. The car was the star attraction at every stop; movie stars, politicians and other dignitaries clamored to pose with the vehicle or take it for a test drive at the invitation of tour organizers. Eleanor Roosevelt and Douglas Fairbanks among dozens of other celebrities were photographed behind the wheel at various ports of call. Police motorcades escorted the celebrity Model A into towns where brass bands heralded its arrival, and locals turned out by the thousands to see the spectacle. States issued one of a kind license plates numbered 20,000,000 to mark the occasion, presenting them to Ford representatives with great pomp and pride. The car even made a few laps and took the checkered flag at Indianapolis Motor Speedway, and became the first private vehicle to descend to the bottom of Hoover Dam for a photo op. It was a welcome season of levity; a brief respite for a nation in the throes of the Great Depression. With automobile sales slumping and Americans in desperate need of a morale boost, Ford could hardly have planned a better public relations campaign. Back in Detroit, the car remained a novelty item for a short time, but the world soon moved on. For many years, the original twenty millionth Model A was presumed to have been destroyed in a fire, along with the registry book logging the tour stops, commemorative state plates, and other souvenirs picked up along the way. But in the 1990s the car was almost miraculously rediscovered in storage, still owned by the family who purchased it from Ford in 1940. The deteriorating sedan underwent a total restoration in the early 2000s to bring it back to pristine, original condition in honor of Ford’s 2003 centennial celebration. The company then leased it for ten years to be displayed at their world headquarters in Dearborn, Michigan. Though the log book and commemorative plates from the national tour have never been found, hundreds of photos documenting the famous Model A’s triumphant, cross-country journey have resurfaced to document that moment in time. Imagine my surprise when one such photograph turned up while I was researching the history of Latta Ford in Selmer. The photo shows a group of McNairy County dignitaries gathered around the Twenty Millionth Ford outside the local dealership. It was taken shortly before Earl Latta purchased the business and broke ground on a new location, 205 West Court Avenue, at what is now the McNairy County Visitor’s and Cultural Center. When the photo was taken, the local dealership, Bolton Ford, was in the 100 block of West Court Avenue, where present day China King is located. This image came to light more than a decade ago, thanks to Nancy Kennedy at the McNairy County Archives. As a young woman, Nancy worked for Earl Latta, so she was always keen to preserve anything related to the history of his successful business ventures. The photo appears to be copied from newsprint with a 1932 date, supplied by an unknown archivist. In all likelihood, that date is one year off, given that the tour concluded in December 1931, and can be documented in Middle and East Tennessee, as early as June of the same year. Inaccurate date or not, it’s a wonderfully evocative photo tying local people to a an historic event of national significance. Part two of this essay will detail how Henry Ford may have inspired a young Earl Latta to indulge his interest in old-time music while refining his sales pitch for Ford motorcars. The four part series, Fords & Fiddles, appears as a guest column by Shawn Pitts in the March 2023 issues of The McNairy County News and on Pitts's blog, Broomcorn with additional links and photos. |

|

|

Photo credits: Huffoto (Arts in McNairy's official photographer)

|

Arts in McNairy | 205 W Court Ave, Selmer, TN | PO Box 66, Selmer, TN 38375 | 731-435-3288| [email protected]

RSS Feed

RSS Feed